Apparently innocent looking animals engaged in a sort of self absorption inhabit predominantly in Prashant Salvi’s paintings. Muted speech bubbles hovering around their heads highlight the sagacious vacancy of their minds. In the absolute absence of thinking, as per Indian philosophy, the individual soul becomes one with the universal soul, realizing godhead to which he/she is an integral part but seen divided in mundane situation. This clear meditative depth that spirals down in the works of Salvi however could be a deceptive methodological tool that the artist forwards for a completely personalized critique of the society in which he lives, which I would qualify as circumstantial critique. Salvi, by doing this through his works, however does not stay there forever and using his creative freedom, he moves in and out of the critique, facilitating the idea of criticality not only within his work but also in his personal life. This creative freedom enables the artist to generate counterpoints of agitation as set against tranquility, violence against piety and unbarred eroticism against the implied de-sexualization of bodies.

As one looks on, the muted animals fade away from the ken of his perception and its place is taken over by a series of imageries, highly and furiously charged with erotic desires verging into the zone of cannibalism and self sustaining homo-erotic playfulness.

In these works Salvi becomes an absent progenitor of images possessed and obsessed with erotic potential. The slow disappearance of animal figures is made possible through the clever introduction of anthropomorphic forms which strangely resemble the male and female genitals. Flowers, frills, uncontrolled growth of shrubs and branches, highly suggestive of erotic nerve ends of human beings, intersperse with animal and anthropomorphic images, bringing forth a series of metaphors loaded with surrealist connotations. Seen in the Freudian point of view, these constantly transforming images, fluid while being sculpturally dimensioned, could suggest the artist’s inner world, the ways of his mind’s working, his fears, anxieties and desires, suppressed for apparent reasons, but refuse to be buried and forgotten. They come back, as the artist approaches his pictorial surfaces, like waves that give a faint hope of subsiding but return with all fury and vengeance. Here, Salvi does not represent his own self alone, on the contrary, he represents a collective self of the society, which he shares, enjoys and at times forcefully resists. In this zone of identification with the collective unconscious of the larger society, the artist plays the role of a Devil’s advocate, deliberately playing up the counter point to the normative and affirmative. Hence, the images that flow out of Salvi’s thoughts may look dark and invested with a strong libidinal drive, which make the works look strangely attractive to the point that one would wonder why this artist is so hooked up with such force of eroticism. Eros, in Salvi’s works fights against Thanatos, as we have seen in the works of many a modern master both in India and abroad. The return of the cruel self, charging towards the sexualized bodies of both men and women, ripping them with all the carnal pleasures possible, then becomes a celebration of life force, the eternal quest to live on using will and libido in full force. This celebration of the cruel self in Salvi’s works may appear to go against the grain of my positioning of his works as circumstantial critique. Interestingly, it is the other way round; in circumstantial criticism and its resultant state of criticality, the generator of it cannot operate as an outsider. He is and he has to be an insider, possessing the social evils and mirroring it for a larger and wider deliberation.

Prashant Salvi in studio

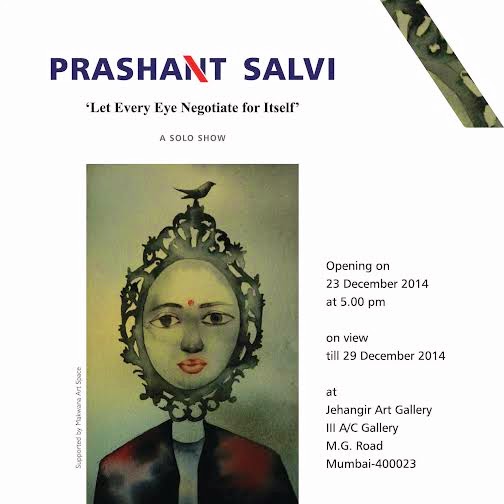

In one of his works, we see a rabbit sitting cozily on a cushion with a mirror hanging and reflecting the other side of its face, while on a red velvet spiral one sees a grey swan with its side wing frames a sharp gazing eye looking at the viewer.

This work obviously sets the tone of Salvi’s circumstantial critique or criticality in which he oscillates between the divine and demonic selves. Rabbits are timid creatures, agile and existential at the same time. Famous for their capacity to reproduce in many numbers, their sexual potency is an understated metaphor here. In this sense, they represent the contemporary human beings who refuse to age. A mirror, especially in a work of art is a representation for human vanity. In this work, the hidden side of the rabbit is seen reflected in the mirror. With naturally frightened eyes, this rabbit with two different faces, one, the ‘seen’ and the other, the reflected, automatically represent a human being, who looks clean and affable but frightened and potent simultaneously. The cushion with blue stripes is evocative of a rich and comfortable life. Swan is a representation of beauty, communication and learning (especially seen from within the Indian context). Salvi makes an intervention here; he places an eye squarely on the body of the grey swan. This eye is the eye of the artist and also the eye of the viewer; one eye becomes mutually reflected two eyes here. To our surprise, we see five eyes clearly drawn in this painting, out of which four are real eyes and one is a metaphorical one. Two eyes of the rabbit, one eye of the swan and the human eye on the body of the swan together make four eyes and the fifth one is the mirror itself. Mirror, an image that comes repeatedly in Salvi’s works, is a philosophical as well as a metaphorical eye. It is a reflection of the self and the eye thatsees the eyes that look at it. This omnipotent eye is the eye of the god who sees everything and reflects everything. Salvi, in this work philosophically sets the tone of all his other works. If what we see around us, including us, are the reflections of an inner eye, then what we call real must be an illusion; something tangible yet intangible. This illusion however is loaded with the knowledge of many other illusions. According to the artist, it is libido that one uses to negotiate with this illusion and make real out of it. And an illusion could be made real only by looking deeply into/at it. The more one looks at the illusion of the world the more one becomes clearer about its trappings.

The more one sees the trappings, the more one becomes liberated from these illusions. Hence a real human being is born. Salvi brings forth the erotic images again and again as an effort to look at these illusions of the world, as if these images were for him like the syllables in a chanting. They are built around the central axis of an eroticized male or female body and their grappling with the illusion is connoted through the possible copulating images, in strange ways and in strange deeds. In this sense, for me, Salvi’s works arelike the erotic ensemble that we see in the facades of Khajuraho and Konark temples. They purge the human beings through desiring gazes and purge them of the evil thoughts before leading them to the sanctum sanctorum of divine existence, which is the human soul itself.

This entry into the core of life, leaving illusions behind is possible only when one is ready to look and see. Looking and seeing could be innocent acts but when applied in an ideologically loaded and culturally constructed (at times genetically malformed) scenario, these aspects of gazing for meaning could be perverse in nature. Gaze itself comes to have negative connotations because of the perversities involved in the agency of gazing. It becomes an ideological positioning of the gazer; looking becomes an act of exercising power over the weaker one for control or pleasure and seeing could be designed at/by convenience. Gaze becomes fornication with eyes, subjecting the gazed to a lower position. Salvi keenly explores this aspect of fornication with eyes as exercised in our society. Despite all sensitizations and awareness programs, our society remains to be predominantly male oriented and gaze is one tool that the male members of the society employ for subjugating the female members. This reduction of women into sexual objects for pure or perverse pleasure, devoid of any aesthetical finesse, becomes a metaphor in Salvi’s works; he aestheticizes what is not aestheticized in gaze. The slow transformation of the crass into an aesthetically sensitive and at times titillating image is what makes the works of Salvi more and more curious on repeated viewing. There is no shying away, as far as Salvi is concerned, from this frontal and unapologetic representation of the erotically gazed, in these works. However, Salvi makes it more sympathetic; without accusing the one who gazes and yet not victimizing the one who is gazed at, Salvi takes a shrink’s point of view and tries to see how this aspect of gaze operates in our society. He builds up some interesting images that are surreally transformed, in order to present his points, which he says that he is unable to escape from forwarding. In his works, young and old men and women, animals, birds, flowers and everything turn into metaphors of erotic gaze. Metamorphosis of the male body in a Kafkaesque way into eroticized organic forms/creatures is one of the metaphors that come repeatedly in Salvi’s works. The eye fornication done by older men with no devices to subsist on for quenching their sexual desires other than these subdued forms of voyeurism consolidates into the form of a torso and lower body clad in traditional male clothes, often riding on certain erected and thorny forms, looking for softer openings to penetrate. Birds appear quite often in Salvi’s works not only as the messengers of god’s words but also as a symbol of human mind that keeps on digging the dirt for pleasure. Digging of any sorts, in Salvi’s works, is brought in as an auto-erotic symbolism. Against this active principle of birds, Salvi sets up mute animals like Donkeys who are real prisoners of their own un-deployable potency.

Recent Artwork by Prashant Salvi

Salvi is a master of colours and design. In his pictorial surfaces, he creates arange of colours which are not often seen in the works of other contemporary artists. They are never bright as in a sunny day nor are they dark in a gloomy cloudy day. They are the colours that exist in the minds of those creative artists that see the colours lay there between the accepted norms of colour usage followed by moderate artists. His palette is more classical and stands closer to those of the masters like El Greco (16th C AE) and Vermeer (17th AE). The Mannerist usage of colours in our contemporary times looks fresh in Salvi’s works and the subject matters that he deals with in his works get an added veneer through such skillful manipulation of colours. His palette, in many ways defines the mood of our times; a time that reveals a lot of glittering ephemerals but hide the dark recesses of mind. Salvi makes an interesting balance of both in his works. He maintains the surface glitter to the point that it could reveal the depth of what is implied. The suggestive nature of his works heralds the arrival of a new artist of our times. Design of space and the employment of visually available designs within that designed space are two highly commendable hallmarks of Salvi’s works. The starkness of the images is often softened by these design elements that he incorporates not only as a background but also as an integral part of the work. Animals prowl, petals flutter, birds fly and dig around and muted speeches anchor well in the deep silence that pervades the world- in this world of novelty and strangeness, men and women celebrate their inner life, angelic, devilish, erotic and potent at the same time. Prashant Salvi is the eye that witnesses.

Mumbai/ December 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for comment JK